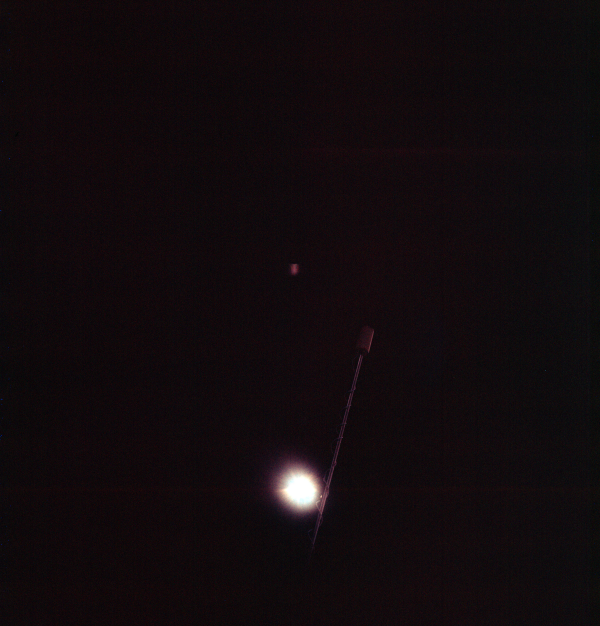

The total solar eclipse of November 1966, as seen by the Gemini 12 astronauts while in space. Credit: NASA

On Nov. 12, 1966, totality sliced across South America. Its progress began north of Peru’s capital, Lima, before forging a 52-mile-wide (84 kilometers) southeasterly swath of totality to plunge northern Chile and Bolivia, the foothills of northwestern Argentina and Paraguay’s rural southwest, and almost as far as the southern tip of Brazil, into an ethereal gloom for as much as 117 seconds.

The grandeur of a total solar eclipse, as the Moon passes directly in front of the Sun and briefly blots out its life-giving warmth, is an otherworldly experience. At totality, as the last vestiges of sunlight linger at the rugged lunar limb, the effect is akin to a diamond ring, with only the Sun’s glowing corona still visible. And across a narrow patch of Earth below, the path of totality imposes a darkness and a primeval reverence so profound that even we science-savvy 21st-century dirt-dwellers are left awestruck.

But on that Saturday almost six decades ago, as people gazed upward and the Andean morning sky dimmed prematurely, two men watched the proceedings from above. Gemini 12 astronauts Jim Lovell and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans in history to witness a total eclipse from beyond Earth.

Gemini’s crew

If not for a cruel quirk of fate, Aldrin may never have had a seat on Gemini 12 to see it. Astronaut assignments followed a predictable formula: A backup crew for a given mission tended to rotate into a prime crew three flights later. But when Aldrin and Lovell were named as Gemini 10’s backup crew, they knew theirs was a dead-end assignment, for Project Gemini ended at Gemini 12, with no Gemini 13 to aspire to.

All that changed in February 1966, when Gemini 9 prime crewmembers Elliot See and Charlie Bassett died in an aircraft accident. They were replaced by their backups and all subsequent crews (prime and backup) moved up in the pecking order. Lovell and Aldrin became the new Gemini 9 backups, which gave them a shot at flying Gemini 12, the last in the series.

In his memoir, Men from Earth, Aldrin reflects on his sadness at gaining a flight seat at the expense of losing Bassett, his Nassau Bay, Texas, neighbor and close friend. “That was how I came to have a mission assignment,” Aldrin writes. “It was a hell of a way to get one.” Yet Bassett’s widow, Jeannie, was sympathetic. “Charlie felt you should have been on that flight all along,” she told the dejected Aldrin. “I know he’d be pleased.”

Shifting objectives

With Gemini 12 set to launch from Cape Kennedy’s Pad 19 on Nov. 9 , a secondary mission objective (time permitting) was to photograph the eclipse as Lovell and Aldrin flew over the Galapagos Islands on their 39th orbit. Totality would occur at 63 hours and 48 minutes into their four-day flight. Aldrin was already scheduled to perform a stand-up extravehicular activity (EVA) in Gemini 12’s open hatch and would document the eclipse with a 16-millimeter motion-picture camera and 70-millimeter still camera.

Then fate intervened again. A malfunctioning power supply in Gemini 12’s Titan II rocket delayed launch until Nov. 11, a two-day slip which caused the moment of totality to shift squarely into the midst of a block of crew time when Lovell and Aldrin would be busily raising their orbit from 185 to 460 miles (298 to 740 km), using the main engine of the docked Agena target spacecraft. Disappointingly, the eclipse observation was scratched from the flight plan. But not for long.

At 3:46 P.M. EST on Veteran’s Day, Gemini 12 speared into space and Lovell and Aldrin docked with the Agena four hours later. But the intended orbit-raise to 460 miles was canceled when flight controllers observed an anomalous decay in the Agena’s thrust chamber pressures and a drop in turbopump speeds. Mission Director Bill Schneider and Flight Director Glynn Lunney deemed prudence to be the safer form of valor and opted not to risk firing the Agena’s main engine.

With this change to the flight plan, the option to observe totality reentered consideration, thanks to Gemini 12 Experiments Advisory Officer James Bates. The crew were thrilled.

“The eclipse got to us after all,” Lovell gleefully radioed.

“Yep, looks like it,” replied astronaut Pete Conrad from Mission Control.

A new perspective

Seven hours after launch, Lovell fired the Agena’s secondary engine to slightly slow their velocity and achieve adequate phasing of their orbit to photograph the eclipse. But the computer-controlled burn fell shy of its required accuracy and a second burn at 15 hours after launch nudged Gemini 12’s apogee a little higher to furnish the astronauts with a better chance of capturing totality on film.

Sixteen hours, one minute, and 44 seconds after leaving Cape Kennedy — “right on the money,” according to the crew — the eclipse came into view for a photo op like no other. Lovell had fitted an extra filter into his window for added protection from the Sun’s glare as he aligned Gemini 12 for Aldrin’s cameras.

Though Aldrin snapped several photographs and acquired 32 feet (9.75 meters) of footage, the brevity of the event, coupled with a low Sun angle, meant he could not photograph the shadow of totality as it fell across the southern Americas. But post-flight calculations showed that Gemini 12 passed within 3.4 miles (5.5 km) of the center of the umbra.

Luck or not?

The rest of Gemini 12 ran with the crispness of a military campaign. By the time the spacecraft splashed down in the western Atlantic Ocean on Nov. 15, Aldrin set a record for the greatest amount of spacewalk time: more than 5.5 hours.

Eclipses, whether partial or total, have been observed for millennia, their cause variously attributed to godly angst; harbingers of impending conflict; or portents of plague, famine and malcontent. But if eclipses like the one seen by Lovell and Aldrin really are heralds of misfortune, there remains one curious footnote from Gemini 12’s story: Had See and Bassett not lost their lives in February 1966, it is unlikely that Lovell would have flown the first manned voyage to the Moon on Apollo 8 or commanded the “successful failure” of Apollo 13. And it is even less probable that Aldrin would have entered pole position for a seat on Apollo 11 and a place in history as the second man to walk on the lunar surface.

Maybe the total eclipse witnessed by the pair that day, nearly 60 Novembers ago, was not such a portent of bad luck after all.