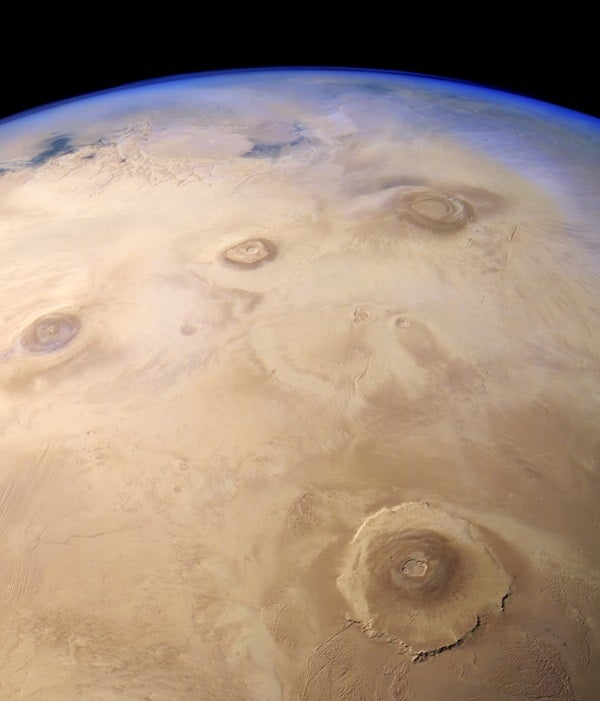

Four massive volcanoes make up the Tharsis Bulge on Mars. The largest of the four, Olympus Mons, is at bottom right. Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin/Justin Cowart.

Four massive volcanoes make up the Tharsis Bulge on Mars. The largest of the four, Olympus Mons, is at bottom right. Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin/Justin Cowart.

Young Mars would have been a staggering place to explore. The Red Planet was covered in flowing rivers of both water and lava. At the time, a series of four volcanoes — Olympus Mons and the three peaks of Tharsis Montes — were all growing taller than any mountain on Earth.

Each of these peaks is impressive. But Olympus Mons stands above the rest, reaching an astonishing height of 16 miles (26 kilometers), or around three times as tall as Mount Everest. That makes Olympus Mons the largest volcano in the solar system.

However, appreciating it requires an understanding that the volcano isn’t just tall. It’s also got girth. Olympus Mons is about 20 times wider than it is high. Its diameter spreads 370 miles (600 kilometers) from edge to edge.

If you set Olympus Mons on top of the United States, it would cover the entire state of Arizona. And if you plopped it over Europe, it would cover France. A 2011 study suggested that the volcano contains roughly one million cubic miles (4 million cubic kilometers) of material, which truly dwarfs anything on our own planet. That’s around 100 times the volume of Earth’s largest volcano, Mauna Loa.

Olympus Mons sits on the same volcanic “bulge” as the three volcanoes of Tharsis Montes — Ascraeus Mons, Pavonis Mons, and Arsia Mons.

And when four mega volcanoes formed so close together it proved to be more weight than Mars’ surface could bear. The volcanoes made the planet tip over a bit. Some 3 billion years ago, Mars’ outer layers slipped under their weight. The crust and mantle traveled about 20°, moving from the polar regions toward the equator. It was enough to reroute rivers and change the planet’s climate.

Earth volcanoes vs. Mars volcanoes like Olympus Mons

How did Olympus Mons grow so big? Time.

It is a shield volcano, which means it oozes huge amounts of lava, rather than simply blowing its top in a catastrophic eruption. Earth’s biggest volcanoes are also shield volcanoes. This lets them grow slowly over time.

However, Earth’s plate tectonics also spread magma out, which keeps terrestrial volcanoes from indefinitely growing taller. Mars, on the other hand, is too small for plate tectonics.

Olympus Mons is some 3.5 billion years old, which means the volcano formed early on in Mars’ history. Astronomers suspect Olympus Mons could have stayed volcanically active for hundreds of millions of years. That’s far longer than any volcano on Earth could remain active.

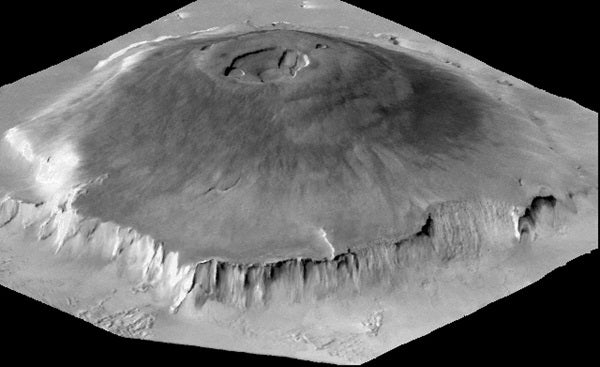

Clues to Mars’ climate history A 3D image of Mars’ massive volcano, Olympus Mons, which is the largest in the solar system. Credit: NASA.

A 3D image of Mars’ massive volcano, Olympus Mons, which is the largest in the solar system. Credit: NASA.

In a Nature Communications paper published in 2017, astronomers studied a family of meteorites called nakhlites, which were all flung from Mars when an asteroid struck a volcano on the Red Planet some 11 million years ago.

The study showed that Mars’ volcanoes were seeping lava at a seriously slow pace: The volcano that formed the nakhlites grew 1,000 times slower than volcanoes do on Earth. The finding implies that Mars’ volcanoes last longer than scientists previously expected.

And in Olympus Mons’ case, the craters on its surface are also only around 200 million years old, which implies this volcano was active surprisingly recently, at least to a limited extent.

By studying Olympus Mons and other volcanoes on Mars, scientists can help unravel clues to the Red Planet’s climate history, too. The meteorites born from the volcano actually show signs of minerals that form as water passes through rock, which suggests water was flowing on Mars as recently as 1.3 billion years ago. So, it turns out, the Red Planet’s era of running rivers and flowing lava might not have only been confined to the extremely distant past.